The word reflux literally means “backflow.” Laryngopharyngeal reflux, or LPR, is the backflow of stomach contents up the esophagus and into the throat. The injurious agents in the refluxed stomach contents (refluxate) are primarily acid and activated pepsin, a proteolytic enzyme needed to digest food in the stomach. The damage caused by these materials can be extensive. The above picture displays a diffusely inflammed larynx secondary to LPR. Specific findings include laryngeal hyperemia, posterior commissure hypertrophy, pseudosulcus vocalis, and thick endolaryngeal mucus.

LPR is different than gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Patients with GERD are usually seen by a gastroenterologist. They typically suffer from heartburn and many pertsons with GERD have esophagitis. Although some persons with LPR do suffer from heartburn or esophagitis (12%), most persons with LPR do not. The reason for this is that the refluxate spends very little time in the esophagus and does most of its damage in the larynx. The anatomic abnormality in patients with LPR is thought to exist at the level of the upper esophageal sphincter. Esophageal motility and esophageal acid clearance are usually normal. The esophagus is very well equipped to handle small amounts of reflux and little, if any esophageal injury occurrs in patients with LPR. Because patients with LPR do not suffer from heartburn, the diagnosis may be difficult to make for some clinicians. Referral to a specialist may be necessary.

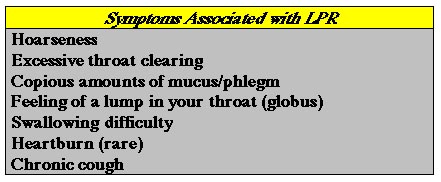

Symptoms caused by refluxed stomach contents are numerous and include hoarseness, cough, and chronic throat clearing. LPR can also affect the lungs and may exacerbate asthma, emphysemsa, or bronchitis. The table below displays some of the symptoms caused by LPR.

We have validated a 9-item reflux symptom index (RSI) to assess the initial severity of LPR symptoms as well evaluate patient response to treatment. A RSI greater than 10 may indicate significant reflux. Please feel free to complete the RSI below.

Reflux Symptom Index (RSI)

A RSI > 10 could indicate significant laryngopharyngeal reflux

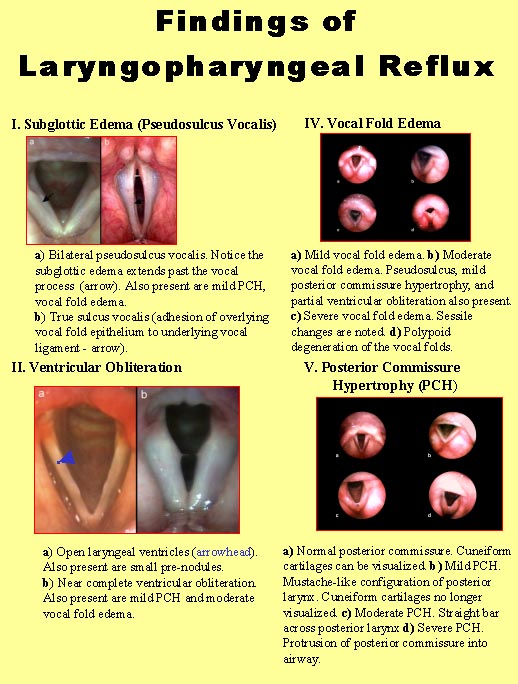

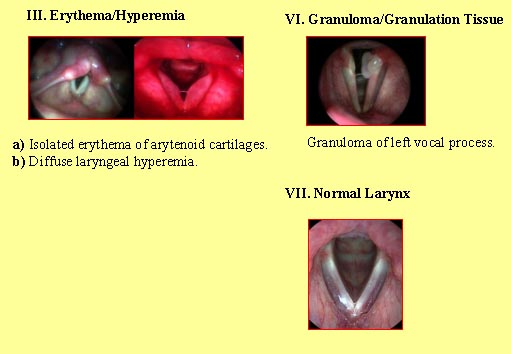

The tissue injury to the larynx caused by LPR has previously been poorly described. The laryngeal findings of LPR are summarized below. After evaluating these images, it is easy to see how the voice and swallowing mechanism can be severely effected by LPR.

The diagnosis of LPR may be made by any combination of history, physical examination and 24-hour pH probe testing. A reflux symptom index (RSI) greater than 10 may be indicative of significant LPR. Physical findings of LPR are displayed above. In some patients the history and physical examination findings may be equivocal. 24-hour pH testing may be indicated. For this diagnostic test a small catheter is placed through the nose into the throat and esophagus for a 24 hour period. The catheter has multiple sensors on it to detect the presence of acid in the esophagus and throat (drop in pH < 4). The patient wears the catheter with a small computer recording device on his/her waist home and comes back to the office the next day to have the readings interpreted and the catheter removed. This test is very useful in patients with recalcitrant LPR, those failing medical therapy, and those considering surgical intervention such as fundoplication.

Treatment for LPR includes any combination of behavioral modification, pharmacotherapy (medications), and surgery. Behavior modification includes weight reduction, avoidance of food high in fat and caffeine and elevation of the head of the bed.

Medical therapy for LPR includes nonprescription antacids and H2 antagonists such as Maalox, Mylanta, Pepcid and Zantac. Gum chewing increases salivary production and may help neutralize regurgitated stomach acid. Although these medications are often effective at treating GERD, they are often ineffective at treating LPR. Proton pump inhibitors (Prilosec, Prevacid, Aciphex, Protonix, Nexium) are more potent medications than antacids and H2 blockers. In sufficient quantities they can result in complete acid supression. Relatively high doses over an extended period of time (6 monthhs or greater) may be required to reverse the tissue injury to the larynx.

Surgical options for treating LPR are usually reserved for medical treatment failures as well as younger individuals with severe LPR who face a lifetime of expensive medical therapy with unknown long term consequence. Surgical options include minimally invasive procedures such as radiofrequency ablation of the lower esophageal sphincter as well as endoscopic Nissen Fundoplication which is a procedure where the surgeon wraps the stomach around the distal esophagus to create a tight valve. It has proven to be very successful in preventing reflux into the esophagus as well as the pharynx (throat) and larynx. Please see our section on reflux therapy.

Esophagopharyngeal reflux (EPR) is the regurgitation of esophageal contents back into the larynx and pharynx. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is the disorder caused by the regurgitation of GASTRIC contents into the esophagus. The hallmark of GERD is heartburn. LPR is the disorder caused by the regurgitation of GASTRIC contents into the larynx and pharynx. Persons with GERD and LPR usually respond well to medications that reduce the acid content of the refluxed materials (H2-blockers/proton pump inhibitors). Patients with EPR present with symptoms very similar to persons with LPR. They do not, however, respond well to traditional anti-reflux therapy. The problem with EPR is that of bolus transport and esophageal emptying. Most patients with EPR have a disorder of esophageal motility. Some of the ingested food sticks in the esophagus and regurgitates back into the throat causing throat clearing, cough, excessive mucus, etc… Treatments for EPR are similar to treatments for esophageal dysmotility. Treatment for EPR is often less successful than treatmment for LPR or GERD. Medications that reduce the acid content (H2-blockers/PPIs) do not stop static esophageal contents from being regurgitated back into the upper airway. Behavioral modifications are crucial and alginates (Gaviscon) have shown some success in keeping the food contents from regurgitating out of the esophagus. persons with a diagnosis of LPR who fail medical therapy should be considered for a diagnosis of EPR. A dynamic video-fluoroscopic swallow evaluation and ambulatory impedance testing are the only ways to diagnosis EPR.

The following video clips are fluoroscopic and endoscopic images of reflux: