James A. Koufman, M.D., F.A.C.S.

Director, Center for Voice Disorders

And Professor of Otolaryngology

Wake Forest University School of Medicine

Winston-Salem, North Carolina 27157-1034

www.thevoicecenter.org

Peter C. Belafsky, M.D., Ph.D.

Director, Center for Voice and Swallowing Disorders

University of California at Davis Medical Center

Department of Otolaryngology/Head and Neck Surgery

Sacramento, California 95817

www.ucdvoice.org

“How many people do you see walking around limping because it’s fun to limp

or they are too stupid to walk right?” – Jamie Koufman. M.D.

This is our model of behavioral voice disorders.

“She sang so loudly in the cold night air that she destroyed her voice forever.”

Can a single insult lead to permanent vocal fold damage? “With training, his voice will be fine.” Do people with voice problems have predominantly behavioral problems i.e. they don’t know how to use their voices properly? What are the most common causes of voice problems? These questions are the subjects of this article, and things are not always what they seem.

We have adopted the B.I.N.N. model of voice disorders based on a prospective analysis of 200 consecutive patients with laryngeal and voice disorders. Not all of these patients were singers, but many were professional voice users such as clergy, actors, teachers, telephone operators, etc.

TABLE 1 : THE B.I.N.N. MODEL

- Behavioral (90%)

- Inflammatory (70%)

- Neoromuscular (30%)

- Neoplastic (20%)

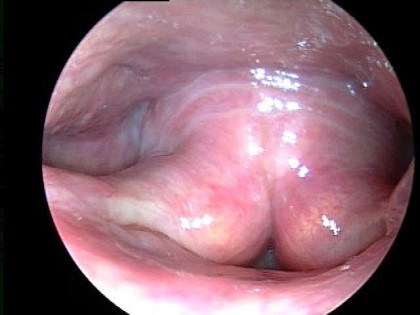

Figure 1. Normal laryngeal closure. The shape of the larynx looks rather like first position in ballet. When a person has bad technique–hard glottal attack, poor breath stream control, muscle tension, and vocal abuse–laryngeal biomechanics degenerate and become hyperkinetic. These muscle tension patterns are created by excessive muscular activity of other laryngeal and neck muscles, and the vocal folds become partly obscured by structures above, such as the false vocal folds; see Figure 2.

Figure 2. Muscle tension pattern 4 secondary to severe vocal fold paresis.

The reality is, however, that most people with abnormal laryngeal biomechanics, (laryngeal muscle tension), do not have primary behavioral voice disorders. So perhaps the word “behavioral” is incorrect, or perhaps needs redefinition. What is “behavioral,” and how often do people misuse or abuse their voices?

The answer to the question, even for singers, is usually found outside the singing arena. While there are singers who abuse their voices – most commonly those who sing rock and gospel- this is infrequently the cause of vocal problems.

In 1995, we characterized the effort (muscle tension) required to perform different singing styles (1). We evaluated the laryngeal biomechanics of 100 singers from 8 different singing varieties. The findings are displayed in Table 2. Choral singers had the least amount of laryngeal muscle tension and rock and gospel had the highest muscle tension scores. All study subjects were mostly healthy singers with no vocal complaints. Thus, we concluded that even if a singing style was associated with lots of laryngeal muscle tension, this observation had little to do with voice problems, i.e., singers working at the limits of their voice use numerous muscles and often push them hard without any adverse consequences.

So what does “behavioral” mean? In reality, there has been an evolution of our thinking since the time when we as voice clinicians tended to blame patients for their ills. Yes, as recently as twenty years ago, we thought that vocal misuse/abuse was the most frequent cause of voice disorders. Now, we have loosened the tern “behavioral” to mean either misuse or compensation. What is meant by compensation? When we observe abnormal laryngeal muscle tension (i.e., abnormal biomechanics), this is most often not due to vocal misuse, poor technique, or abuse, but rather to compensatory laryngeal behaviors from an underlying neuromuscular disorder.

Most of the time, abnormal laryngeal biomechanics are due to the fact that there is an underlying problem with one or both of the vocal folds. In other words, many times we compensate for problems without even thinking about it; bad biomechanics are usually compensatory for an underlying vocal fold problem. What are these problems? How common are they? And how often are these diagnoses being missed? Are the problems themselves treatable? How useful and important are voice therapy and voice training?

Voice training and therapy are imperative, for they allow an individual to perform as efficiently as possible within his or her innate ability. Behavioral voice therapy or voice training cannot, however, correct vocal fold paralysis or some other underlying medical condition.

As many as 90% of patients with abnormal laryngeal biomechanics have an underlying organic disorder and not vocal misuse, poor technique or abuse.

The letter I in B.I.N.N. represents inflammatory disease. Laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR), the backflow of stomach contents into the throat, is ubiquitous and often silent (2). By silent, we mean that the patient has no awareness that such events are occurring. Specifically, most patients with LPR do not have heartburn. In a study of 113 patients with laryngeal and voice disorders, silent reflux was found in half (3).

Interestingly, 88% of people with growths on the vocal cords had reflux and 70% of patients with previously diagnosed “behavioral voice disorders” also had LPR.

LPR is the great masquerader. In our practice we have seen singers whose careers were ruined by LPR and yet the diagnosis was never made or at the very least, they were never effectively treated. Other entities cause inflammation such as radiation exposure, pollutants, allergy and upper respiratory infections. Surprisingly, allergies are a very uncommon cause of laryngeal inflammation. Environment pollutants can, however, cause laryngeal inflammation and irritation.

The first N in B.I.N.N. represents neuromuscular disease. This refers to vocal fold paralysis, paresis (partial paralysis), or some other neurological problem. This topic has been a focus of research at the Center for Voice Disorders for the past five years, and we have found that a substantial number of patients with so called “behavioral voice disorders” actually have underlying vocal fold paresis (4). In other words, one or both vocal folds can be weakened by some prior event such as placement of a breathing tube, trauma and upper respiratory infection so that the vocal folds are no longer capable of closing completely without additional effort. This disorder requires state-of-the-art diagnostic equipment including acoustical analysis and laryngeal electromyography [LEMG] (5). The latter is a test in which a small needle (like acupuncture) is placed into the muscle of the larynx to measure the electrical current.

The last N in B.I.N.N. represents neoplasia. Laryngeal neoplastic disorders are simply any growths within the larynx (Figure 3). The most common laryngeal neoplasms are vocal nodules, cysts, polyps, granulomas, and cancer.

Figure 3. Paresis podule on mid-portionof right vocal fold causing hoarseness ina professional voice user.

A discussion of these neoplastic lesions is beyond the scope of this article; however, a brief discussion about vocal fold “screamers” nodules is prudent. Many laryngeal neoplasms that are diagnosed as nodules are NOT! Prenodules, for example are inconsequential, symmetrical, vocal fold swellings that are fleshy and rarely significant. They are common.

True vocal fold nodules are usually the consequence of an underlying disorder, not the cause. Therefore, surgical removal of symmetrical vocal fold nodules is seldom recommended. When nodules are asymmetric, however, they take the form of a cyst, callus, or bunion (Figure 3). They are usually associated with underlying vocal cord paresis (weakness) and usually require surgery. Thus, the distinction between symmetric and asymmetric vocal fold “nodules” is crucial.

If you refer to Table 1 you will notice that 90% of patients with voice disorders have a behavioral component to their disorder. The larynx tries very hard to adapt to any underlying weakness, and nearly all patients with voice disorders present with hyperkinetic (hard-working) compensatory vocal behaviors i.e. they have abnormal biomechanics (Figure 2). In addition, 70% of patients with voice disorders have inflammatory disease (mostly reflux i.e. LPR); 35% have vocal fold weakness (paresis), and approximately 20% have vocal fold growths. The key to understanding our data is that the average patient with a voice disorder has two or more diagnoses. In other words, a patient with vocal fold nodules might also have LPR and an underlying vocal fold paresis.

While there is no question that voice therapy and vocal training can improve vocal performance and glottal efficiency to an optimal level, such treatment cannot overcome certain underlying laryngeal problems. Indeed, in the above-cited article on singing (1), we found that the muscle tension scores of trained singers were lower than those of untrained singers. So training helps.

So what is the message one should take home from this article? Many people who have problems with their voices have underlying vocal fold paresis (weakness) and/or LPR.

It is important to recognize that “glottal closure symptoms” such as effortful phonation, painful speaking or singing, vocal fatigue, and breathiness are not just signs of vocal misuse or abuse. In many cases, there is an underlying organic problem.

The modern Voice Center now has four component laboratories; videostrobocropy, acoustical analysis, reflux testing, and laryngeal electromyography. Each of these provides diagnostic information that no other test can provide. If you are having problems with your voice and you are not getting the outcome you want, you should seek care at a center that has state-of-the-art diagnostics.Most of the conditions mentioned above can be treated and corrected. Although laryngopharyngeal reflux is different than classical gastroesophageal reflux disease (LPR patients don’t have heartburn usually), treatment with medication is usually successful. In addition, for people with vocal cord weakness, there are now surgical procedures, which can restore the voice (6).

In treating people with voice disorders, to get successful outcomes, each of the underlying problems must be identified and corrected.

REFERENCES

Koufman JA, Radomski TA, Joharji GM, Russell GB, Pillsbury DC. Laryngeal biomechanics of the singing voice. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 115:527-537, 1996.

Koufman, JA, Postma, GN, Cummins, MM, Blalock, PD. Vocal fold paresis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 122:537-541, 2000.

Belafsky PC. Abnormal endoscopic pharyngeal and laryngeal findings attributable to reflux. Am J Med. 2003 Aug 18;115(3 Suppl):90-6.

Belafsky P, Postma G, Koufman J. The association between laryngeal pseudosulcus and laryngopharyngeal reflux. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002 Jun;126(6):649-52.

Koufman JA, Postma GN, Whang CS, Rees CJ, Amin MR, Belafsky PC, Johnson PE, Connolly KM, Walker FO. Diagnostic laryngeal electromyography: The Wake Forest experience 1995-1999. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001 Jun;124(6):603-6.

Koufman J, Belafsky P. Unilateral Reinke’s edema and localized Reinke’s edema (pseudocyst) as a manifestation of vocal fold paresis. Laryngoscope 2001;111:576-580.

Belafsky PC, Postma GN, Reulbach TR, Holland BW, Koufman JA. Muscle tension dysphonia as a sign of underlying glottal insufficiency. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2002 Nov;127(5):448-51.

Koufman JA, Amin M, Panetti M. Prevalence of reflux in 113 consecutive patients with laryngeal and voice disorders. Otolaryngeal Head Neck Surg 123:385-388, 2000.

Koufman JA, Walker FO: Laryngeal electromyography in clinical practice: Indications, techniques, and interpretation. Phonoscope 1:57-70, 1998.

Postma GN, Blalock PD, Koufman JA: Bilateral medialization laryngoplasty. Laryngoscope 108:1429-1434, 1998.

Postma GN, Koufman JA: Laryngeal electromyography. Current opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery 6:411-415, 1998.

Koufman JA, Blalock PD. Functional voice disorders. In: Koufman JA, Isaacson G, eds. Voice Disorders. Otolaryngol Clin N Amer 24:1059-1073, 1991.

Koufman JA, Isaacson G. Laryngoplastic phonosurgery. In: Koufman JA, Isaacson G, eds. Voice Disorders. Otolaryngol Clin N Amer 24:1151-1171, 1991.

Koufman JA. Medicine in the vocal arts. N C Med J 54(2):79-85, 1993.

Koufman JA, Blalock PD. Vocal fatigue and dysphonia in the professional voice user: Bogart-Bacall syndrome. Laryngoscope 98:493-498, 1988.